Photography has long been thought of as a way to capture reality, a means of freezing a moment in time exactly as it was. But can an image ever be completely objective? The idea that a camera sees everything without bias is, frankly, a bit of a myth. Behind every image is a photographer making choices—what to frame, what to leave out, what to highlight, what to suppress. Even when a photographer aims to be a passive observer, their presence, perspective, and intention inevitably shape the final image.

Let’s break it down. Imagine a street scene. A bustling market, people rushing about, vendors shouting out their offers, the smell of fresh bread in the air. You’re there with your camera, looking for the shot. Now, even before you press the shutter, you’re making choices. Do you focus on the weary stall owner, counting their change with a tired expression? Or the vibrant energy of a street performer dazzling a small crowd? Maybe you step back and capture the whole chaotic scene in a wide-angle frame. Whichever moment you choose, you’re telling a specific story. The market, the people, the noise—it’s all there, but you decide which version of that reality to present.

Framing and Composition: The Photographer’s Invisible Hand

Even documentary photographers, whose job is to capture events as they unfold, bring their own biases. What they choose to include, where they stand, and what they leave out all influence how the audience perceives the scene. A war photographer, for example, might focus on a child’s tear-streaked face, emphasising the human cost of conflict. Another might capture a soldier sharing a quiet moment of camaraderie, presenting a different narrative. The event itself doesn’t change, but the photographer’s choices define how it is seen.

Then there’s the issue of perspective—literally. Where a photographer stands physically impacts the final image. A low-angle shot makes a subject appear powerful, dominant. A high-angle shot can make them seem small, vulnerable. Step in close with a wide lens, and the viewer feels immersed, part of the moment. Stand back and zoom in, and suddenly, there’s a sense of detachment, of observation rather than participation. These aren’t just technical choices; they shape the emotional response to an image.

The Impact of Intent and Emotion

Intention also plays a massive role. Is the photographer aiming to inform, to provoke, to inspire? Even photojournalists, bound by ethics to report honestly, must decide what to prioritise. A protest, for instance, can be depicted as a peaceful gathering of citizens demanding change, or as a chaotic clash between demonstrators and police. Both might be true, but the way they are framed influences public perception. It’s not about deception—it’s about the unavoidable influence of perspective.

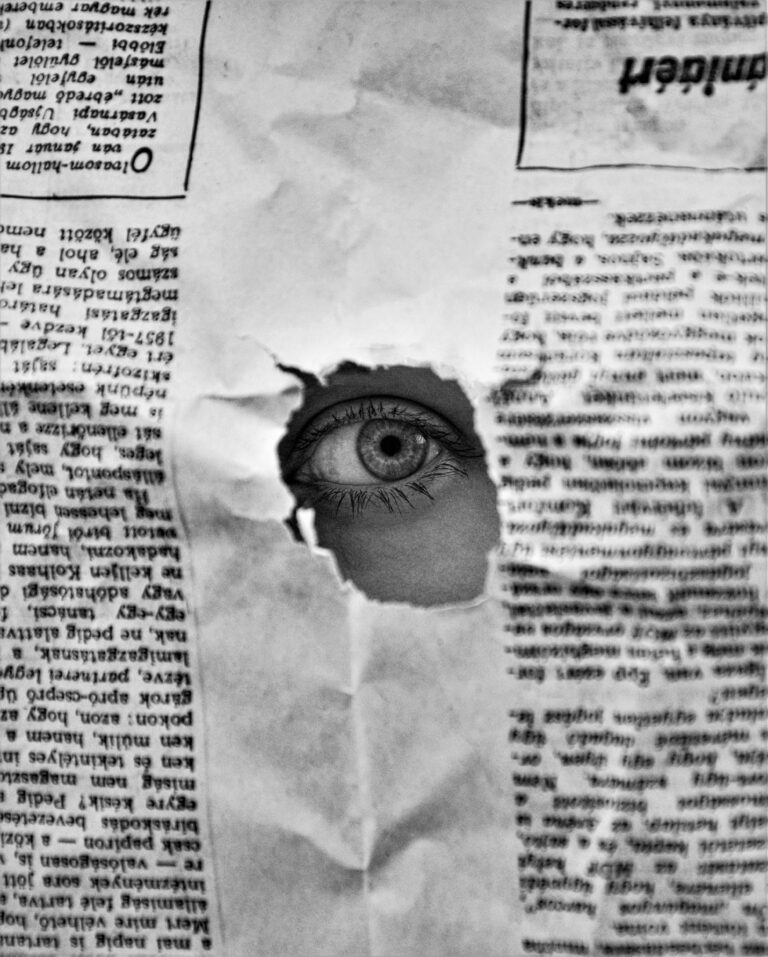

Even the act of choosing to take a photograph is an intervention. The moment a photographer lifts their camera to their eye, they’re altering the environment. People notice. A candid smile might become forced, a child’s natural playfulness suddenly stiffens into self-consciousness. Some photographers go to great lengths to be invisible—shooting from the hip, using small cameras, blending into the background—but the very presence of a lens changes things, even subtly. The observer is never truly unseen.

The Role of Editing: A Second Layer of Interpretation

Then there’s editing. Post-processing has always been part of photography, from dodging and burning in the darkroom to adjusting contrast and colour balance in digital software. A slight tweak in brightness can shift an image’s mood dramatically. A black-and-white conversion can turn a mundane street scene into something timeless, dramatic. Cropping can reframe an image entirely, removing context or drawing attention to a specific detail. Editing isn’t necessarily about deception—it’s about emphasis. And emphasis is subjective.

Take a famous example: Robert Capa’s iconic war photographs. Gritty, blurred, full of movement—they feel raw, immediate, real. But was that purely accident, or intentional framing? What about Steve McCurry’s ‘Afghan Girl’? The piercing green eyes, the tattered red scarf—it’s an incredible image, but it’s also composed to maximise emotional impact. Every element in a powerful photograph has been considered, whether consciously or instinctively.

The Myth of the Neutral Observer

Of course, some photographers deliberately lean into subjectivity. Fine art photographers, conceptual photographers—they embrace interpretation, creating images that provoke thought rather than document fact. Even in commercial photography, choices in lighting, styling, and retouching all shape how products, people, or places are perceived. Nothing in an image is ever truly neutral.

One of the most famous debates about objectivity in photography revolves around the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Known for his concept of the decisive moment, he believed that capturing the perfect fraction of a second in an unfolding scene was what made a photograph powerful. But even within that philosophy, he had to decide which moment to capture, when to click the shutter. The choice to wait for the “perfect” moment instead of simply documenting a sequence of events is itself an act of subjectivity.

Some argue that objectivity might be possible in automated photography—surveillance cameras, satellite imagery, or traffic cameras. These devices don’t have intent or bias; they simply record. But even then, a human decides where to place the camera, how frequently it captures images, and what gets saved or discarded. The moment a decision is made, objectivity is compromised.

Final Thoughts: Embracing Subjectivity in Photography

So, can an image ever be truly objective? In a word—no. The photographer is always present, whether in the moment of capture, in the framing, in the edit. Even the most honest, unfiltered snapshot carries a perspective. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing. It’s what makes photography an art, a form of storytelling rather than just recording. Understanding this doesn’t diminish the power of photography—it deepens our appreciation for it. The next time you look at a photograph, ask yourself: what choices were made here? What story is being told? And, just as importantly, what’s been left out?

Rather than striving for impossible objectivity, perhaps the true power of photography lies in awareness of its subjectivity. Acknowledging the photographer’s role in shaping what we see allows us to engage with images more critically and thoughtfully. Whether it’s a news photo shaping public opinion, a wedding picture capturing joy, or a street shot revealing everyday beauty, every photograph is a collaboration between reality and the person holding the camera.

Keywords for SEO:

- Can photography be objective

- Objectivity in photography

- Photographer bias in images

- How photographers shape perception

- Subjectivity in documentary photography

- Impact of framing in photography

- Photojournalism and objectivity

- Editing and photography bias

- The role of perspective in photography

- Photography as storytelling

- Influence of intention in photography

- Can a photograph be neutral

- The decisive moment in photography

- How composition affects an image

- Photography and truth

- The unseen photographer’s influence

- Manipulation in visual storytelling

- The myth of unbiased photography

- Emotional impact of photography

- Reality vs perception in photography